Modernist British Prints : In Association with Osborne Samuel

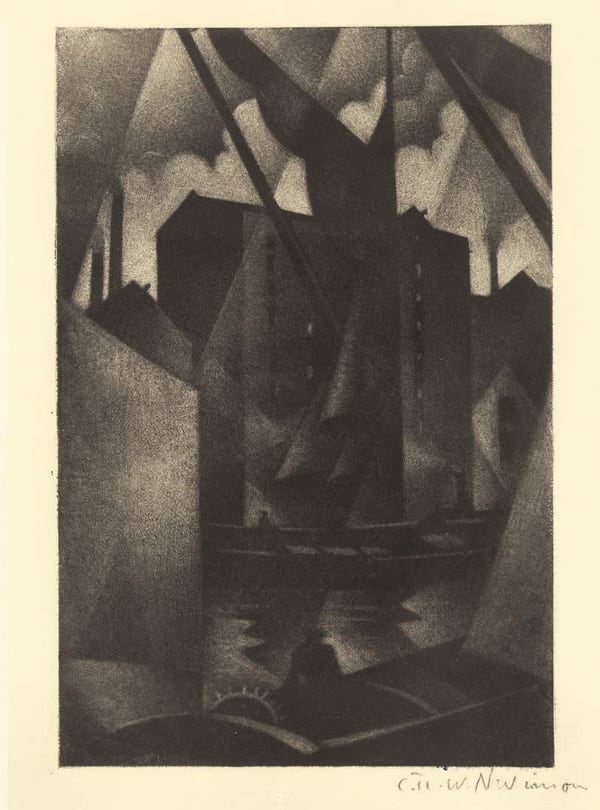

In the pre-war years, artists were responding to the rapid modernisation of time and in anticipation of what would be the first fully mechanised war. French Cubists were reacting to the changing times by including abstract shapes and fragmentation in their work. Italian Futurists perceived the world as being in a constant state of flux so further incorporated a sense of dynamism and fluidity. Britain’s answer was Vorticism which typically favoured more precise lines, sometimes reminiscent of architectural drawings. Vorticism was seen as the first radically modern and inherently British art movement.

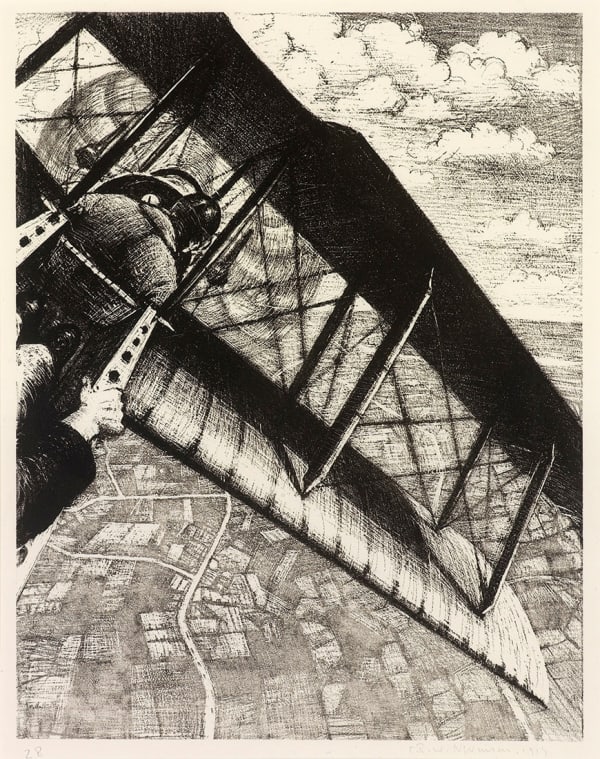

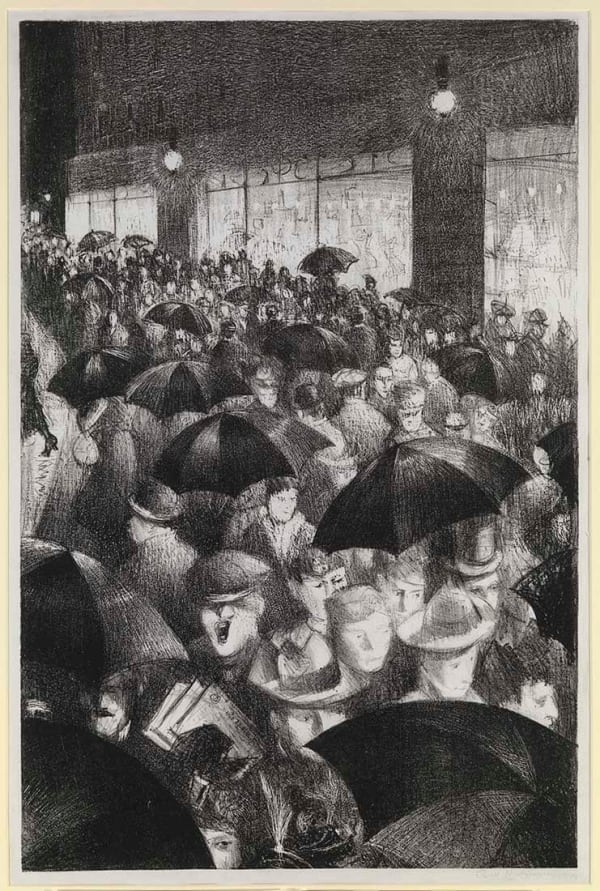

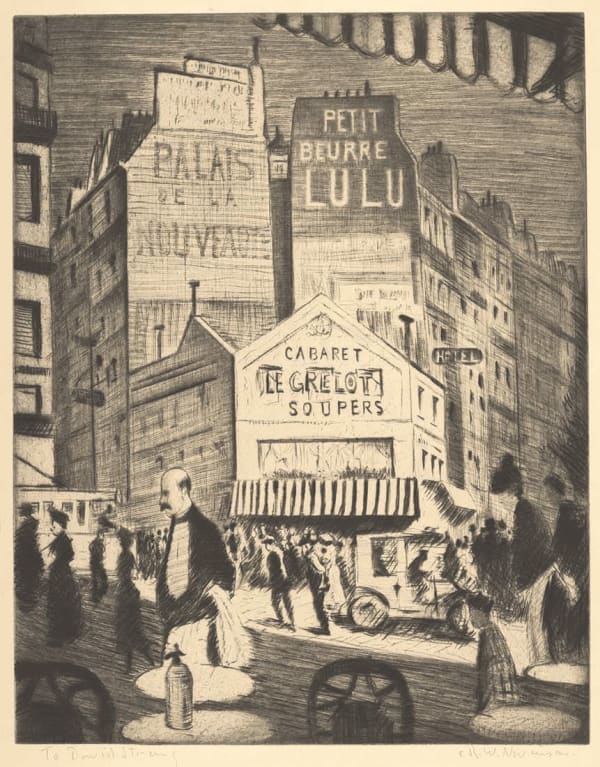

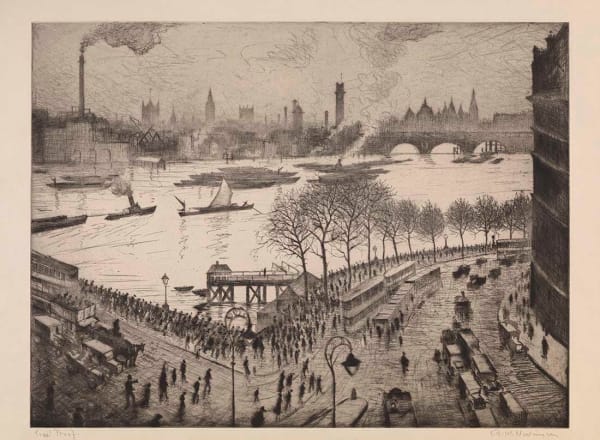

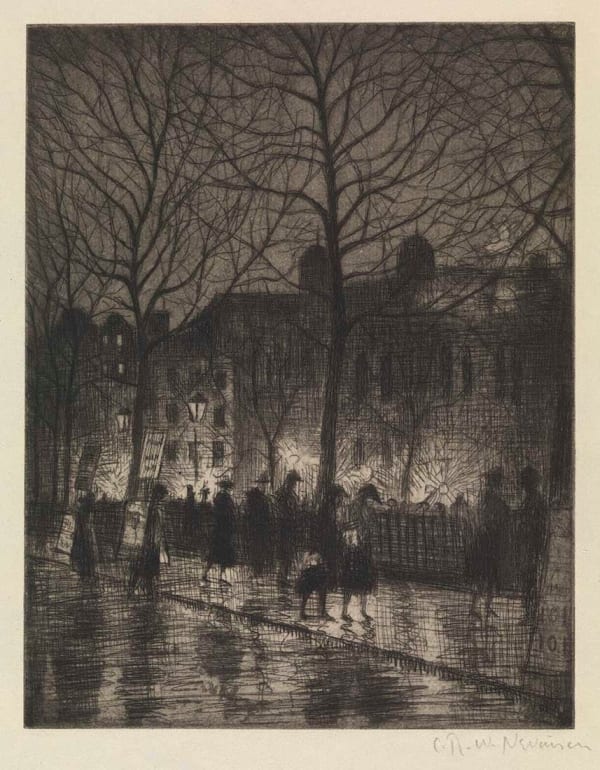

London-born CRW Nevinson (1889-1946) identified as a Futurist therefore he believed war was a necessary and useful tool to bring about change. Upon serving however, he witnessed extreme human suffering and realised the brutal reality of war. This conflict of ideology and experience is apparent in his work. Some works are bleak and somber depictions of the mechanised war, presenting soldiers as anonymous bodies as opposed to heroic individuals. Others, including Banking at 4000 feet, are more in-keeping with his Futurist roots and illustrate the thrill of riding a flying machine allowing him a God’s-eye view of the landscape below. The images of London he made after the war were at a time when he was becoming disillusioned with radical modernism. His style grew more natural, with less abstraction and a single-point perspective.

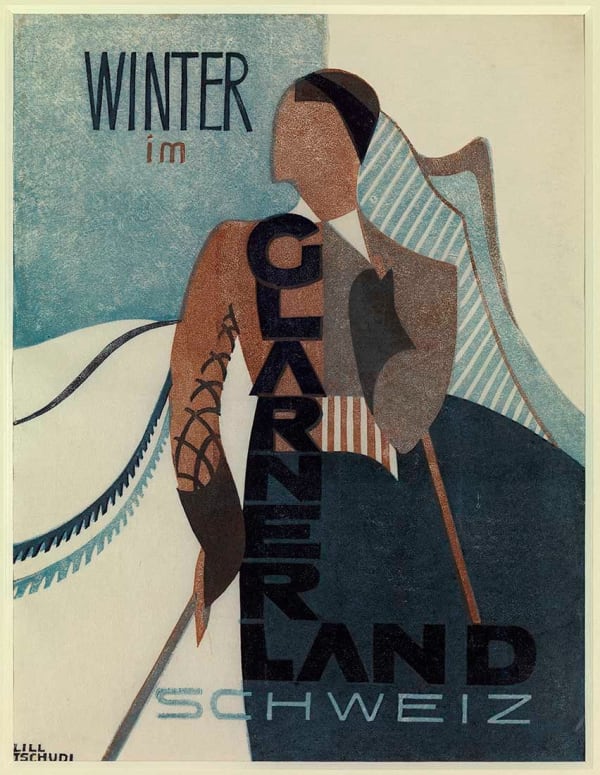

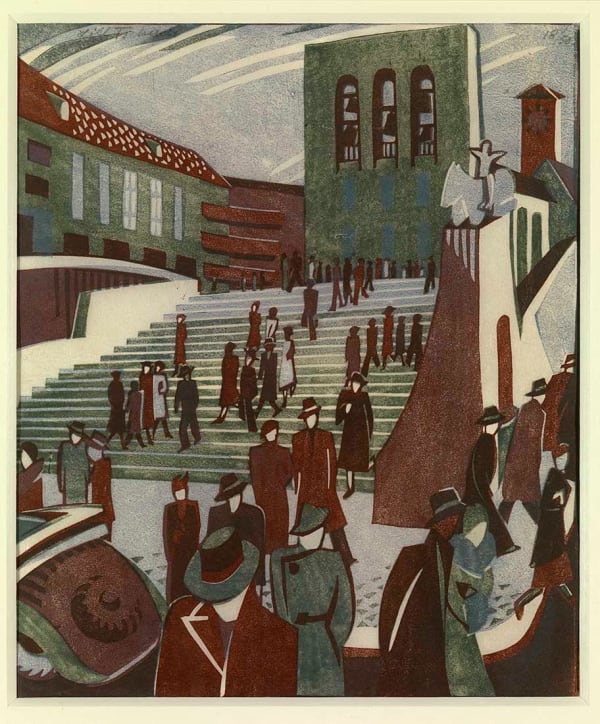

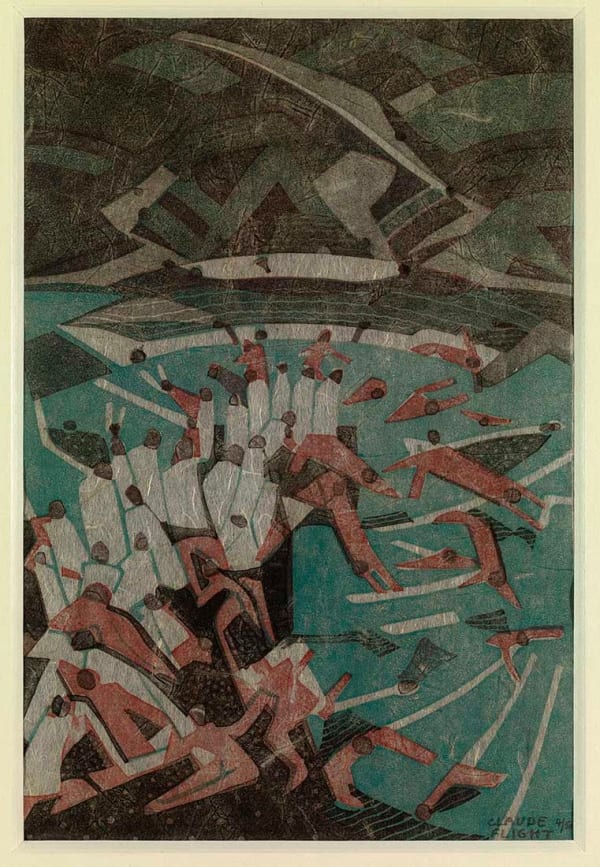

The Grosvenor School of Modern Art (1925-1940), a private art school in London with no formal curriculum, was a major player in the Modern British Printmaking scene. Claude Flight (1881-1995), a friend of CRW Nevinson, taught a class in Linocut. His students included Cyril Power (1872-1951), Sybil Andrews (1898-1992), Lill Tschudi (1911-2004) and Ethel Spowers (1890-1947). At the time, linocut was mostly used as a tool to introduce children to printmaking but Flight identified it as an exemplary tool for artists to respond to the new machine age. Early 20th century modern artists were also particularly fascinated with the simplicity and freeness of children’s artistic expression

The Grosvenor School predominantly explored themes of sports, urban life and industry. It saw London as the epicenter of an accelerating world of machines and modern living. Irony and humour often runs through Power’s work, mocking the modern amenities of modern life. In Runners he makes use of the rhythm and repetition of the athletes to reduce them to automatons. Sybil Andrews was less predisposed with movement than her peers so shapes take a more geometric form. In Hayel, the bodies of the workers mimic the shape of their tools in order to become one. In Tschudi’s Dancers, the figures revolve around a central point much like a cog. Tschudi’s works vary in style, but like all of the Linocut artists, abstraction remains a constant. Spowers used a more delicate representation of movement than her fellow graduates. In The Plough, she presents her subject empathetically, stooped and tiring.